Principles of T'ai Chi Ch'uan by Master Zhang Sanfeng

Ripening Peaches: Taoist Studies and Practices

How to Live a Good Life: Advice from Wise Persons

Taoist Grand Master Chang San-Feng

The Tao

of Tai-Chi Chuan: Way to Rejuvenation (1980) by Master Jou, Tsung Hwa

History, Folklore, and Legends

Taoist Master Chang San-Feng (Zhang Sanfeng)

One tradition claims that Master Chang San-Feng was born at midnight on April 9, 1247 CE, near Dragon-Tiger Mountain in Kiang-Hsi Province in the southeast of China. He is said to have been a government official in his youth, learned Shaolin martial arts while living in the Pao-Gi Mountains near Three Peaks (San Feng), and then lived for scores of years as a Taoist priest, healer, and sage at the Wudang Mountain Taoist Temples (Wutang, Wu Tang Shan). He is reported to have lived to be 200 years old (1247-1447 CE), but his death date is uncertain. He would have lived in the Sung, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties if these dates were accurate. (Jou, 1980)

Another tradition claims that there were two Master Chang

San-Feng Taoist priests and sages.

One

was born in the Sung dynasty (960-1279 CE), lived on Wudang Mountain as a

recluse, and

combined

the thirteen postures with other Taoist practices and arts to create a style of

internal martial

arts that became popular amongst the Taoists living and studying at Wudang

Mountain. The second Master Chang San-Feng (1279-1368), was a native of I-Chou in LiaoTung Province. His scholarly

name was Chuan Yee and Chun Shee. He also lived on Wudang Mountain and

was a highly regarded Taoist Master and scholar with many amazing magical,

divinatory and healing powers. He lived a very long life and was

very popular with the local people.

Master Chang is known by a variety of names: Chang San-Feng, Cheng San Feng, Chang Chun

Pao, Chang Sam Bong, Zhang Sanfeng, Chang Tung, Chang Chun-pao, Grandmaster

Chang, Chang the Immortal, Immortal Chang, Zhangsanfeng, Zhan Sa-Feng,

Zhan Jun-Bao, Yu-Xu Zi, Chuan Yee and Chun Shee. There may have been a number of male Taoist

priests and hermits who

chose to use the name Chang San-Feng.

Some legends have made Chang San Feng into a Xian (Hsien)

仙

仚

僊. A

Xian is a Taoist

term for an

enlightened person, an immortal, an alchemist, a wizard, a spirit, an inspired

sage, a person with super powers, a magician, or a transcendent being. A Xian 仙

is similar in function to a Rishi who is an inspired sage in the Indian

Vedas. I myself consider Chang San Feng, Master Chang, to be a Xian in my

poems.

"Xian are immune to heat and cold, untouched by the elements, and can fly, mounting upward with a fluttering motion. They dwell apart from the chaotic world of man, subsist on air and dew, are not anxious like ordinary people, and have the smooth skin and innocent faces of children. The transcendents live an effortless existence that is best described as spontaneous. They recall the ancient Indian ascetics and holy men known as rishi who possessed similar traits."

- Victor Mair, Wandering on the Way

The early legends about Master Chang San-Feng are linked with activities of Emperor

Chengzu

(1403-1424) who searched for Master Chang and other political refugees. By 1459,

Master Chang

had been declared an Immortal and, as with most saints, stories of his

miraculous

powers became part of the folklore in the Wudang Mountain area. There is a

fairly

long tradition amongst Wundang Mountain martial artists and Taoists that attributes the

development

of soft style martial arts to Chang San-Feng and his disciples

(Yeo, 2001; Wong Kiew Kit, 1996). In 1670,

Huang Zongxi wrote a book

called Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan in which Chang San-Feng was called the founder of internal martial arts practiced near Mount Wudang.

By the

1870's, Yang family Tai Chi Chuan teachers were claiming that Chang San-Feng was the originator of

Tai Chi Chuan. (Wong, 1997; Wile, 1996; Bing YeYoung, 2006.)

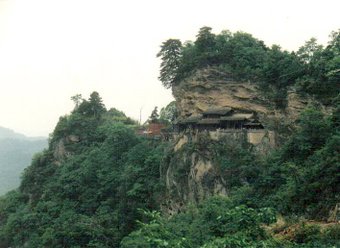

Wudang Mountain

(Wudangshan 武当山) has many Taoist temples, monasteries, and facilities.

It has been an renowned academic center since 700 CE. It has long been associated

with Taoist studies and practices, Taoist scriptures, traditional Chinese medicine, herbal

research, agricultural arts, meditation, unique exercises to increase

longevity, and internal martial arts. Zhang San Feng has been linked with most aspects of

this Wudang

culture.

More recently, some scholars and tai-chi historians have argued that Chang San-Feng

had

little or nothing to do with the founding of Tai Chi Chuan or internal martial

arts. They

contend that this aspect of the Master Chang legend was invented in the late

19th

century by Yang family stylists to give their art form deeper historical

roots. (Wile, 1996;

Tang Hao, History of Chinese Wushu, 1935; Henning, 1981; and Siaw-Voon Sim, 2002; Bing YeYoung, 2006;

John Bracy, 2008.)

These authors

contend that the Tai Chi Chuan systems

(i.e., forms, push hands, sword/staff, chi

kung exercises,

and Taijiquan principles) as

we

know them today (e.g., Chen, Yang, Wu, Hao, Sun), were all created as successive

variants to the system developed by the military leader and martial artist Chen Wangting

(1600-1680)of Chenjiagou Village in Henan Province.

My own view is that the Taoist Master Zhang San Feng was a

real person, living around 1200 CE. He traveled extensively, and like any

sensible long distance walker in those days, was skilled in martial arts for

self defense (probably including using the sword and/or staff). He enjoyed

learning from different Taoist, Confucian and Buddhist teachers. He likely stayed for some

length of time at the Shaolin Temple and at Taoist centers on Mt. Hua and

finally at Mt. Wudang. He was very reclusive, and disregarded social

proprieties. He was a highly respected Taoist master of

internal energy arts,

a defensive and "internal" style of martial arts, alchemy, mysticism, and philosophy. His deep knowledge,

high moral character, writings, and high level of skills attracted many Taoist

followers who continued his mind-body Taoist practices, studied writings attributed to him, and

told and retold stories (many apocryphal) about Master Zhang over the past 900

years.

People in China, Tibet, and India have for millennia used exercises to improve

health,

cure disease, restore vitality, and increase lifespan. Gentle stretching,

breathing

methods, herbal remedies, and use of postures for exercise can be traced

back over 4,000 years. Martial arts training methods, of course, are of similar

antiquity.

Good old Master Chang, like the Bodhidharma of Shaolin fame, are just reference

points for the imagination steeped in these many centuries of martial

arts, health exercises, and the history of Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.

At another level, Master Chang, Han

Shan, and the Bodhidharma are also examples,

archetypes if you will, of the crazy saint, wise fool, sage, healer, shaman, and wandering

recluse

that contrasts so markedly with the ordinary family-society lifestyles of the vast

majority in any culture or civilization. The Buddha himself, after

military training

in his youth, left his family

life to

wander and live the life of a solitary ascetic and mystic for a decade.

So, we

sometimes

look to these fellows, real and imaginary, and ask them "So, old man, what

have

you learned that can help us?" We listen to their advice, and

sometimes follow their recommendations. Sometimes we laugh at them and bang their

copper hat. In moments of whimsy, religious fervor or

desperation, we give some of them, like Chang San-Feng or Chang Po-Tuan, magical

and marvelous powers - to disappear and reappear at will, powers to cause rain to fall,

powers to prevent disaster, powers to chase away malevolent spirits, shamanistic skills, techniques for defeating our enemies, methods

for calming our troubled souls, and amazing skills at divination. Most important, and what intrigues most

folks, is that these hermit seers might hold the secrets for living over 150 years in

good health, or rising from the dead, or pointing to the Way for us to attain eternal life as an Immortal - a Chen Jen: Realized Being.

"Breathing Out -

Touching the Root of Heaven,

One's heart opens;

The Dragon slips by like water..

Breathing In -

Standing on the Root of Earth,

One's heart is still and deep;

The Tiger's claw cannot be moved.

As you go on breathing in this frame of mind, with these associations,

alternating

between movement and stillness, it is important that the focus of your mind does

not shift. Let the true breath come and go, a subtle continuum on the

brink

of existence. Tune the breathing until you get breath without breathing;

become

one with it, and then the spirit can be solidified and the elixir can be

made."

- Chang San-Feng, Commentary on Ancestor Lu's Hundred-Character

Tablet

Translated by Thomas Cleary, Vitality,

Energy, Spirit: A Taoist Sourcebook, 1991, p. 187.

Poetic interpretation by Mike Garofalo of expository text of

Chang San-Feng.

Return to the Main Index for this Webpage

![]()

Bibliography and Links

Master Chang San-Feng

Above the Fog. Poems by Michael P. Garofalo

Advanced Yang Style Tai Chi Chuan. Volume One: Tai Chi Theory and Tai Chi

Jing. By Dr. Yang, Jwing-Ming. Boston, Massachusetts, Yang's Martial Arts

Academy,

YMAA, 1986. Glossary, 276 pages. ISBN: Unknown. The

"Tai Chi Chuan Treatise"

by Chang San-Feng is shown in Chinese, translated into English, and

commented by Dr. Yang on pages 213- 216.

Ancestor Lu's Hundred-Character Tablet

Commentary by Chang San-Feng.

Chang

San-Feng and Wudang Mountain

Chang San-Feng: His

Life and Deeds. By Jack McGann and Christopher Dow. An

apocryphal biography of the legendary founder of Tai Chi Chuan. An

interesting short biography with some new stories about Master Zhang.

Chang San-Feng, Taoist

Master. Brief biography, links, bibliography, quotations, and a study

of the "Treatise on Tai Chi Chuan". Compiled by Michael P.

Garofalo. Includes poems and commentary

by Mike Garofalo. Red Bluff, California, Green Way Research.

Chen

Style Taijiquan: The Source of Taiji Boxing. By Davidine Siaw-Voon Sim

and

David Gaffney. Berkeley, CA, North Atlantic Books, 2002. Index,

charts, 224 pages.

ISBN: 1556433778. Provides an excellent introduction to

Chen style Taijiquan

history and legends, outlines the major forms, discusses the philosophy and foundations of the art.

Cloud Hands: Taijiquan

and Qigong Website

Cold Mountain Buddhas (Han

Shan)

The

Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan: A Comprehensive Guide to the Principles

and Practice. By Wong Kiew Kit. Shaftesbury, Dorset, Element, 1996.

Index,

bibliography, 316 pages. ISBN: 1852307927. Zhang San Feng, pp.

18-22.

Commentary on Ancestor Lu's Hundred-Character Table by Chang,

San-Feng

Cuttings: Haiku and

Short Poems

|

Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu

For each of

the 81 Chapters: Daodejing 81 Website |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dao House: Of Discourses and Dreams "A compendium of links to great online Daoist (Taoist) resources." An excellent selection of fine links with informative and fair annotations; all presented in an attractive and easy to read format. The in-depth and creative collection of links are arranged by 18 topics.

The

Essence of T'ai Chi Ch'uan: The Literary Tradition. Translated and

edited by

Benjamin Pang Jeng Lo; Martin Inn, Robert Amacker, and Susan Foe.

Berkeley,

California, North Atlantic Books, 1979, 1985. 100 pages. ISBN:

0913028630. The "T'ai Chi Ch'uan Ching" by Chang San-feng is translated on pages

17-27.

Evolution of

Taijiquan from Shaolinquan. Written by Sifu Zhang Wuji, Instructor,

Shaolin Wahnam, Singapore.

The Founder

of Wudang Tai Chi Zhuan - Zhang San-Feng

Heavenly Pattern of Boxing. Article by Wong Yuen-Ming.

"Please check the new Journal of

Cinese Martial Studies out of Hong Kong. The editor Wong Yuen-Ming has

written a very interesting paper on the "Heavenly Pattern of Boxing", concerning

non-governmental writings on Zhang Sanfeng. They have a website to find sources.

(Email from Hermann, 8/11/2012)."

The

History and Legend of Tai Chi Chuan. By Dick Watson

History of Yang Style Tai Chi

Chuan. By Craig Rice.

The Immortal Zhang San Feng.

Published by PureInsight.org. This is just an unauthorized and

unattributed copy of an older copy of this webpage by Mike Garofalo.

Index to a Short

Review of the Art of T'ai Chi Ch'uan. By R. W. Watson.

Investigations into the Authenticity of the Chang San-Feng Ch'uan-Chi.

The Complete Works of Chang San-Feng. Faculty of Asian Studies Monographs,

1997. Australian National University. Authored by Wong Shiu Hon.

Ignorance, Legend and Tai

Chi Chuan. By Stanley Hemming. Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 1-7.

23Kb.

Let a Hundred Flowers

Bloom. By Jay Dungar.

Literati

Tradition: The Origins of Taiji. The Origins of Tai Chi - The Chang

San Feng Camp.

By Bing YeYoung. A well researched article. Includes bibliographical

references.

Lost

T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty. By Douglas Wile.

State University of

New York Press, 1996. ISBN: 079142653X. Index, charts, bibliography,

233 pages. The

most detailed and scholarly account of Tai Chi Chuan classics available.

Analysis and

translation of many new texts. Chang San-feng texts are found on pp.

86-89, and discussion

about the historicity of Chang San-feng on pp. 108-111.

Master Chang San-Feng

Legends and Lore, Quotations, Links, Poems.

Meetings with Master Chang San Feng - Poetic Reflections

Mount

Wudang Abode of the Immortals and a Martial Monk

Mount Wudang and

Wudang Kung Fu

The Mythical

Life of Chang San Feng. By John Hancock. 36K. An

excellent informative article.

"A New Look at T'a Chi Origins." By Alex Yeo. T'ai Chi,

Volume 25, No. 4, pp.21- 27,

August, 2001.

One Old Druid's Final

Journey: Notebooks of the Librarian of Gushen Grove

The Origins

of Tai Chi - The Chang San Feng Camp. Literati Tradition: The Origins

of Taiji.

By Bing YeYoung. A well researched article. Includes bibliographical

references. 36Kb.

Return to the Main Index for this Webpage

Plexus: History and Myth Interesting collection of facts and observations about Mt. Hua in China.

Portraits of Chang San Feng: First,

Second -

color, Third,

Fourth, Fifth

Principles of Taijiquan by Chang San-Feng

Refining the

Elixir: The Internal Alchemy Teachings of Taoist Immortal Zhang Sanfeng.

Translation and commentary by Stuart Alve Olson. Phoenix, Valley Spirit

Press, 2013.

"Refining the Elixir is one of the clearest and most in-depth analyses on

Internal Alchemy (Neidan) in English. Aside from the excellent translation work,

Stuart Alve Olson provides extensive introductory sections and commentaries on

the texts—a wonderful guide for practicing and learning the meditation art and

science of Internal Alchemy. Stuart addresses the mystical terminology of

Internal Alchemy by explaining it in understandable, detailed, and practical

terms. Anyone, no matter the tradition of meditation followed, will find this

book inspiring and enlightening. Four important works by Zhang Sanfeng

(Three Peaks Zhang) are provided, along with commentaries: The Great Process for

Refining the Elixir Treatise, Verses on Seated Meditation, The Sleeping

Immortal, Zhang Sanfeng’s Commentary on Lu Zi’s One Hundred Word Discourse.

These four works of Zhang Sanfeng outline clear perspectives on the Taoist

practice of Internal Alchemy, a unique and effective system designed for the

development of health, longevity, and immortality. Zhang Sanfeng, a Taoist

priest of the twelfth century, is not only credited with the creation of Tai Ji

Quan, but with some of the greatest Internal Alchemy texts. He reportedly lived

170 years, from the late Song dynasty through the Yuan and into the early Ming

dynasty. Zhang’s life exemplified the Chinese ideal of a true “cloud wandering”

immortal. His internal alchemy and meditation texts reveal not only his deep

wisdom, but his great influence on Taoism and the teachings leading to

immortality."

Ripening Peaches: Taoist

Studies and Practices

The Rootless Tree. Attributed to Chang San-Feng.

The

Shambhala Guide to Taoism. By Eva Wong. Boston,

Shambhala, 1997. Index,

appendices, 268 pages. ISBN: 1570621691.

Song of Silent Sitting. Attributed to Taoist

Master Chang San-Feng. Taken from the book "The Secret of Training the Internal Elixir in the Tai Chi

Art."

Sword (Jian):

Links, bibliography, quotes, notes.

T'ai-Chi. By Cheng Man-ch’ing and

Robert W. Smith. 1966.

T'ai Chi Ch'uan

Ching. By Chang San Feng. Researched by Lee N. Scheele.

T'ai Chi Ch'uan Classics

Researched by Lee N. Scheele.

T’ai Chi Ch’uan For Health and

Self-Defense. Philosophy and Practice.

By Master T. T. Liang. Edited and with a foreword by Paul B. Gallagher.

Revised, expanded edition, 1977. New York, Vintage Books, 1974, 1977.

133 pages. ISBN: 0394724615. Includes a translation and commentary

on the Treatise, pp. 17-22.

Tai Chi Chuan: History and

Origins

Tai-Chi Chuan in Theory and Practice. By Kuo

Lien-Ying. 1999.

T'ai

Chi Classics. By Waysun Liao. New translations of three

essential texts of T'ai Chi Ch'uan with commentary and practical instruction by Waysun Liao.

Illustrated by the author. Boston, Shambhala, 1977, 1990. 210 pages. ISBN: 087773531X. A

translation and commentary on the "Treatise of Master Chang San-Feng" is found on

pages 87-95.

The

Taijiquan Classics: An Annotated Translation. By Barbara Davis.

Includes a commentary by Chen Wei-ming.

San Franscisco, North Atlantic Books, 2004. Index,

notes, bibliography, 212 pages. ISBN:

1556434316.

Taijiquan Classics

Compilation and Comparison. By Almanzo "Lo Ma"

Lamoureux and others. Includes good notes on other translations of Master Chang's Treatise. Sample.

Taijiquan History and Development.

By Peter Lim Tian Tek. Outstanding collection of

webpages.

Taijiquan Jing by Zhang Sanfeng

Tai Ji Quan Treatise: Attributed to the Song Dynasty Daoist Priest Zhang

Sanfeng. By Stuart Alve Olson. CreateSpace Independent Publishing

Platform, 2011. Daoist Immortal Three Peaks Zhang Series. 120 pages.

ISBN: 978-1490345529.

Taijiquan Treatise of Zhang San Feng. Website of Sifu Wong Kiew Kit.

Taoism, Paganism, Nature

Mysticism, Plant Lore, and Magic

Tao of

Health, Longevity, and Immortality: The Teachings of Immortals Chung and Lu.

Translated

with commentary by Eva Wong. Boston, Shambhala Publications, 2000.

144 pages. ISBN: 1570627258.

The Tao

of Tai-Chi Chuan: Way to Rejuvenation. By Jou, Tsung

Hwa. Edited by Shoshana

Shapiro. Warwick, New York, Tai Chi Foundation, 1980. 263

pages. First Edition. ISBN: 0804813574. An excellent comprehensive textbook. A Third Edition is now

available. Information on Master Chang on pages 2-10. Mr. Jou has provided a

translation and commentary on the "Tai-Chi Chuan Lun" or "The Theory of Tai-Chi

Chuan" by Chang

San-Feng on pages 175- 180.

Taoist

Master Zhang San-Feng

Legends and Lore, Quotations, Links, Poems.

Taoist

Meditation: Methods for Cultivating a Healthy Mind and Body.

Translated by Thomas Cleary.

Boston, Shambhala Publications, 2000. 130 pages. ISBN: 1570625670.

Includes Master

Chang's "Taji Alchemy Secrets."

Tao Te Ching (Daodejing) by Lao Tzu (Laozi) Compilation and

indexing by Mike Garofalo.

Treatise on T'ai Chi Ch'uan by Zhang San-feng.

Treatise on Tai Chi.

Translated by Stuart Alve Olsen and found in "Tai Chi Chuan According to the I Ching."

Return to the Main Index for this Webpage

Valley Spirit Taijiquan Red Bluff, California. Instructor: Michael P. Garofalo.

Vitality,

Energy, Spirit: A Taoist Sourcebook. Translated and edited

by Thomas Cleary. Boston,

Shambhala, 1991. 281 pages. ISBN: 0877735190. Translations

of writing

by Chang San-Feng on pages 183 - 216.

Wood Carving of Chang San-Feng

from Tao Arts

Writings on the

Tao by Master Chang Sanfeng

Wudang Inner Boxing and Wudang Taoist Zhang San-feng

Wudang Qigong: Bibliography,

Links, Resources, Lessons, Quotes, Notes

Wudang Taijiquan: Bibliography, Links, Resources,

Quotes, Notes

Wudang Sword Forms: Bibliography,

Links, Resources, Quotes, Notes, Forms

Wudang Taoist

Inner Alchemy Practice

Zhang San-Feng

Legends and Lore, Quotations, Links, Poems.

Zhang, San-Feng and the Ancient Origins

of Taijiquan, Part I. By David Silver. A very interesting and

informative article.

Zhang, San-Feng

and the Ancient Origins of Taijiquan, Part II. By David Silver.

Zhang San Feng Discussion Board

The Zhang San-Feng

Myth by John Bracy

Wu Tang Mountain Area

Return to the Main Index for this Webpage

![]()

Quotations

Master Zhang San-Feng

"Much of the written material about Zhang Sanfeng is mythical,

contradictory, or otherwise suspect. For instance, he is reported to have been born in AD 960, AD 1247, and again in AD 1279. He

is described as being seven-feet tall, with the bones of a crane and the posture of a pine tree, having whiskers shaped

like a spear, and being able to cover 1000 Li in a day."

- Wikipedia

"Aside from being a wise sage, Master Chang

is also known as the Father of the 'Grand Supreme Fist', Tai Chi Chuan. Chang discovered that most Wu Kuen, that is to say martial forms, were

too vigorous and relied too heavily upon the physical strength. It is told that Master Chang, ever observant of Nature,

once witnessed a combat between a snake and a bird. The noise of this contest had disturbed the Master's

devotions, and venturing forth from his modest hut, he witnessed the bird to attack the snake. At each pass, the bird fiercely

pecked and clawed at the snake, however,

the reptile through suppleness and coiling of his form, was able to avoid the

attacks and launch strikes of his own. The bird in his turn circled and used his wings beat the

snake aside when he

struck. Master Chang contemplated upon this experience. That night, as the Master slept, Yu Huang,

the 'Glorious Jade Emperor', visited Chang in his dreams and

instructed him, teaching him the secrets of the Tao that the bird and

the snake innately knew. The next day, Chang sprang up from his sleep wide awake and inspired by his

Celestial Visitor, and immediately set about the creation of a new Martial Art form that relied upon Internal Power, or Chi, at

its root. This art held as its foundation the Truth that 'yielding overcomes aggression' and 'softness overpowers

hardness'. In honor of his divine influences, Chang called his art Tai Chi Chuan, the 'Grand Supreme Fist'. For

this, Master Chang is know as the progenitor of the Wu Tang Ru (schools), so named because they come from Wu Tang Shan

(mountain). These are the Internal Arts, which are juxtaposed to the External Arts, such as Shao Lin Chuan, which relies upon the physical mastery of

the body and development of great strengths.

- John Hancock, The

Mythical Life of Chang San Feng.

Master Chang San-Feng Watches the Fight Between the Bird and Snake

"Most people recognize Chang San Feng as the

founder of T'ai Chi Ch'uan. The Chang San Feng legend can be viewed as having three phases: phase I (prior to 1669) merely claims that Chang was a

Taoist immortal; phase II (after 1669) claims that he founded the "internal" school of boxing; and phase III

(post 1900) claims that Taijiquan originated with Chang. The Chang San Feng legend evolved during the Ming period (1368-1644),

based on the close association of early Ming rulers with Taoism and Taoist priests, whose prophecies had supported

the founder of the dynasty. Little is known about Zhang except that he is described as an eccentric, itinerant hermit

with magical powers, who died once, but came back to life, and whose life, based on varying accounts, spanned a

period of over 300 years. According to

legend, Chang San Feng created a new set of exercises now known as taijiquan in

the Wudang Mountains."

- Ottawa Chinese Martial Arts, Tai

Chi History

"When the winter was really cold and the track outside the temple, where

he practiced was covered with snow, Chang liked to go out and enjoy the snow-covered landscape. Where he had walked there were no footsteps - like no one had walked there. ... It’s also said, that when he was meditating at night, his cultivated energy - the so-called Chi or Jing - would make his coat flap, and the walls around him would shake. This phenomenon

indicates, that his energy had reached its peak. He had obtained the state where his Chi had been transformed into Shen or

Spirit."

- Bjørn Darboe Nissen, Tai

Chi Chuan and the Human Being

"Some have raised the question of Chang San Feng's existence as there is

much legendary material about him. He is recorded by reliable historical documents such as the

'Ming History' and 'The

Ningpo Chronicles' which have no relation to martial arts literature as having

existed and to have created Wudang Internal Boxing arts. This is in line with the

beliefs held at the Wudang Temple itself and one can find much old material pertaining to Chang San

Feng there. According to the available material, Chang lived at the end of the Yuan

Dynasty (1279-1368) and at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)."

- Peter Lim Tian Tek, The

Origins of Tai Chi Chuan

"The legend of Zhang Sanfeng. therefore, evolved in three stages: prior to

1670 , he was known simply as a Daoist immortal; after 1670 he was credited as the creator of

the "internal" martial arts; and after 1900, as the founder of Taijiquan. Emperor Chengzu (1403-1424) contributed greatly to the legend. Zhang was canonized in

1459. The earliest extant reference to Zhang as a master in martial arts appeared in1670

in the Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan, composed by Huang Zongxi, when Chinese

martial art was categorized into an "external" school of Shaolin originated by

the Buddhist monk Damo, and an "internal" school initiated by Daoist immortal Zhang

Sanfeng of Mount Wudang. Li I-yu in his Brief Preface to Taijiquan (1867)

referred to Zhang as the originator of Taijiquan."

- Chen

Style Taijiquan: The Source of Taiji Boxing. By Davidine Siaw-Voon Sim

and

David Gaffney, p. 28.

"Examples of myths believed by large

numbers to be true includes the story of a man named Zhang San-Feng as the

originator of Tai Chi Chuan and the relationship of internal martial arts to the

Wu Tang monastery. In the case of Zhang San-Feng (also written Chang San-Fang),

although often referred to as the founder of Tai Chi, historical evidence does

not support this assertion. According to martial art historian Douglas Wile,

Zhang was first suggested as the originator of Tai Chi in the middle 1800s. The

legend that developed around the Zhang myth is a good entry point for our

discussion of legend mistakenly represented as factual. According to story,

Zhang is believed to have developed a fighting style based on his observations

of, or dreaming about, a fight between a bird of prey and a snake. However,

historians have been unable to ascertain if Zhang, supposedly an alchemist who

lived (depending on the source) in either the twelfth, thirteenth or fourteenth

centuries, ever truly existed. In contrast, historical evidence supports the

founding of Tai Chi Chuan as traceable to the Chen Family Village (or possibly

the Yang Family)-about three hundred years ago.

In much the same way as the Zhang legend, in contrast to what

Chinese historians tell us, the legend of the Wu Tang monastery long ago

captured the imagination of the writers of Chinese comic books and filmmakers as

the place where the internal martial arts were founded and popularly believed to

represent a sort of yin -yang counterinfluence to the famous Shaolin monastery.

An even bigger mess unfolds when one discusses "secret arts" said to derive from

the supposed merging of Buddhist and Taoist "internal energy" practices.

Although the popular fable holds that secret methods were exchanged between

Buddhist monks and Taoist recluses, it is problematic that first, aside from

extremely rare incidences, such as possibly Chan (Zen) Buddhism, no evidence

supports the merging of Buddhism and Taoism into a secret chi energy based cult,

and second, with the exception of Indian and Tibetan tantric practices (see

chapter six, section three), there are no secret Buddhist energetic practices

and no evidence supporting the pop belief that monks secretly practiced and

merged separate "energetic" traditions."

- The Zhang

San-Feng Myth by John Bracy

"Damo wrote the two classics on changing the tendons and washing the

marrow. He taught

men to practice this in order to strengthen their bodies. Then we come to

Yue Wumu Wang

of the Song Dynasty. He added to the discovery of two classics of body

nurturing. He created Xingyi Quan and directed its usage. The principles of Bagua Quan

are also contained

within. This is the origin of the inner family fist arts. During the

reign of Yuan Shunti, Zhang Sanfeng practiced Daoism on Wudang Mountain. He met a teacher of internal

alchemy.

Both of them practiced martial arts that used Post-natal strength. The

function was more than

proper. However, their arts did not harmonize with Qi inside. They

had the potential to cause

injury to the Dan and injure the original Qi. Therefore, they incorporated

the nurturing methods

of the first two classics and use the whole character of the form of the Taiji

circle. They included

the principles of the Ho Diagram and the Luo Book. Pre and Post many

changes. Flowing with natural principles. Created the Taiji Martial Arts. It explains

the mysteries of nurturing

the body. This martial art borrows the form of the Post-natal. It

does not use Post-natal

strength. In moving and stillness, it pure uses natural. It does not

esteem animal vitality.

The idea is for the Qi to transform into spirit."

- Sun Lu Tang, 1919, Study of Taiji Boxing

Translated by Joseph Crandall, 2000, p. 6

"The 'Cave of the Immortal Chang" at West Pass is

traditionally regarded as the site

where Chang San-feng realized immortality. The Fu-kou Gazetteer

says that the people of Fu-kou believe Chang San-feng left his body in the T'ai-chi Temple on

the

Wu-tang Mountains. An image of him may still be seen there. He wore

a copper

cymbal as a straw hat, which he allowed the people of the Fu-kou to strike

without

becoming angry, for he was very good-natured. The people of Wu-yang

also believe that Chang San-feng was a native of Wu-yang and that they have the

exclusive privilege of striking his hat."

- Lost

T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty, translated by Douglas Wile,

p. 110.

"In 1990 the magazine 'The Soul of Wushu' published a series of

articles entitled 'The Original Taijiquan'. One contribution came from the chief Taoist monk of

the Temple Baijun (White Cloud) in Beijing. 'An Shenyuan'. When questioned by reporters,

remarked that, "In the school of Taoism, apart from Zhang Sanfeng, there were

many other talented people who have contributed much to the formulation and development to

Taijiquan."

- R. V. Watson, Index

to a Short Review of the Art of Taijiquan

"Another Zhang San Feng was a native of I-Chou in LiaoTung Province. His

scholar name was Chuan Yee and Chun Shee. He lived in Yuan dynasty (1279-1368).

The Chinese old book Ming History bearing records available in the monastery

on Wudang Mountain does indeed mention him. Descriptions picture him as being seven feet tall, with the bones of a crane and the posture of a pine tree,

whiskers shaped like a spear, winter and summer wearing the same bamboo hat,

carrying a horsehair duster and being able to cover 1000 Li in a day, sometimes

eating 50 Kg food in one meal, sometimes keeping fasting as long as several

months, possessing amazing memory as to recite a scripture fluently after reading it

just one time. The early legends about Zhang San-Feng are linked with

activities of Emperor Chengzu (1403-1424) who searched for Zhang for many years

without results. By 1459, Zhang had been declared an Immortal and, as with most

saints, stories of his miraculous powers became part of the folklore in the Wudang Mountain area. There is a fairly long tradition amongst Wundang Mountain martial artists and Taoists that attributes the development of soft style martial arts to Chang San-Feng and his disciples. In 1670, Huang Zongxi wrote a book called Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan in which Zhang

San-Feng was called the founder of internal martial arts practiced near Mount Wudang.

- Wudang

Taoist Inner Alchemy Practice

"T'ai Chi Ch'üan's theories and practice are therefore believed by some

schools to have been formulated by the Taoist monk Chang San-feng in the 12th century, a time frame

fitting well with when the principles of the Neo-Confucian school were making themselves felt

in Chinese intellectual life. Therefore the didactic story is told that Chang San-feng as a

young man studied Tao Yin breathing exercises from his Taoist teachers and martial

arts at the Buddhist Shaolin monastery, eventually combining the martial forms and breathing

exercises to formulate the soft or internal principles we associate with T'ai Chi Ch'üan and related

martial arts. Its subsequent fame attributed to his teaching, Wu Tang monastery was known

thereafter as an important martial center for many centuries, its many styles of internal kung fu

preserved and refined at various Taoist temples."

- Hans

Wolfgang

"The art Zhang Sanfeng evolved was

certainly better and more profound than the one he had learnt. I believe that

Zhang Sanfeng himself did not give different names to the art before and the art

after his evolution. He just called them, or it as to him they were the same

art, “Shaolinquan”.

Instead of practicing martial art forms (gongfu), energy

exercises (qigong) and meditation (chan) separately, Zhang Sanfeng integrated

all these three aspects into one unity. This was a tremendous contribution to

the whole of kungfu history, for which he is rightly honored as the First

Patriarch of the Internal Arts. We in Shaolin Wahnam are particularly grateful

to this great master for this development.

Later on, to differentiate the distinct type of Shaolinquan

practiced at the Wudang Mountain where Zhang Sanfeng evolved it from the

original version at the Shaolin Temple at Henan, people called it “Wudang

Shaolinquan. Over the years, this term was shortened to just Wudangquan. Much

later when the great master Chen Wang Ting employed yin-yang principles from the

Taiji concept to explain its principles, people called it “Taijiquan”."

-

Evolution of Taijiquan from Shaolinquan. Written by Sifu Zhang Wuji,

Instructor, Shaolin Wahnam, Singapore.

"Joseph Lee in 'The History of Chinese Science and

Technology' remarked, "The name of Zhang Sanfeng is now firmly related with Taijiquan, a major

school of Chinese Wushu". He goes on to say, "if one really wants to track

down the roots of Taijiquan one cannot fail to value Zhang Sanfengs theistic thoughts on

Taoism"

In 'The Origins of Wudang Taiji' Du Yuwan says, "Taijiquan is

generally said to be passed down from Zhang Sanfeng, but when we get down to the roots we find its beginnings further back in history".

- The

History and Legend of Tai Chi Chuan

"Chang San-feng is one of the greatest figures of later Taoist history and

legend, believed to be master of all the arts and arcana of the Way. He is

particularly famous

as the alleged originator of the popular exercise system know as

t'ai-chi-ch'üan

(taijiquan). Like Ancestor Lü, Chang San-feng is also believed to have

attained

immortality in more than a purely spiritual sense, and to have reappeared in the

world

after his supposed physical death. The works attributed to him, again like

those of Ancestor Lü, are also evidently mixed with later additions and in some cases

may be viewed as generic products of a school rather than works of an individual

author. The

Chang San-feng literature shows an amalgamation of Southern and Northern Schools

of Complete Reality Taoism, as well as traces of older Taoist sects

practicing magical arts."

- Thomas Cleary, Vitality, Energy, Spirit: A Taoist Sourcebook,

1991, p. 183

|

Tao Te

Ching |

|||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 |

| 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 |

| 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 |

| 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 |

| 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 |

| 81 | |||||||||

"Zhang Sanfeng was a semi-mythical Chinese Taoist priest who is believed by some to have achieved immortality, said variously to date from either the late Song dynasty, Yuan dynasty or Ming dynasty. His name was allegedly 張君寶 before he became a Taoist.

His Taoist name in Traditional Chinese characters is 張三丰, or 張三豐. Both are Zhāng Sānfēng in pinyin and Chang1 San1-feng1 in Wade-Giles.

Much of the written material about him is mythical, contradictory, or otherwise suspect. For instance, he is reported by different people to have been born either in 960, 1247, or in 1279. He is described as being seven-feet tall, with the bones of a crane and the posture of a pine tree, having whiskers shaped like a spear, and being able to cover 1000 li in a day (roughly 580 km or 350 miles). He is reputed to have worn a straw hat, but one village reports that the hat was actually a cymbal, which only residents of the village (famous for manufacturing cymbals) had permission to sound upon meeting him.

Another tradition associated with the name has him an expert in the White Crane and Snake styles of Chinese martial arts as well as in the use of the Chinese straight sword or jian. According to relatively recent (19th century) documents preserved in the Yang and Wu families, the name of his Taoist teacher was Hsü Hsüan-p'ing, said to be a Tang dynasty poet.

Many today consider Zhang Sanfeng, if not to have been a verifiable

historical figure, to be a legendary culture

hero of sorts, credited as having originated the concepts of nei

chia; soft, internal martial

arts, specifically T'ai

Chi Ch'uan, as a result of a Neo-Confucian

syncretism of Chan Buddhist

Shaolin

Ch'uan with his mastery of Taoist Tao

Yin (qigong) principles. He is also associated in legend with the Taoist monasteries

at Wudangshan

in Hubei

province.

Some sources record two Chinese emperors sending missions to Zhang Sanfeng to ask for his advice, although neither mission is reported to have found him.

Owing to his mythical appearance, his name frequently appeared in Chinese novels and wuxia films of swordsmen as a spiritual teacher and master of martial arts.

Today, Chinese readers are most acquainted with Jin Yong's version of Zhang Sanfeng, thanks to the popularity of his wuxia novels. In his book The Heavenly Sword and the Dragon Saber, Zhang Sanfeng was a former Shaolin disciple in the late Song Dynasty, and born on May 15, 1247 (Day 9 of month 4 in Chinese calendar). He left Shaolin Temple to establish the Taoist monasteries in Wudangshan. In the book he had seven disciples, and was alive until the late Yuan Dynasty.

The T'ai Chi Ch'uan families who ascribe the foundation of their art to Zhang traditionally celebrate his birth date as the 9th day of the 3rd Chinese lunar month."

Wikipedia - Free Online Encyclopedia (Dynamic - Content Changes)

Wu Tang Mountain (Wudangshan)

Taoist Temple

"The peerless master moves with his group from place to place in the

mountains. His small band contains two highly advanced American disciples. After Babaji has

been in one locality for some time he says, 'Dera danda uthao,' 'Let us lift our camp and

staff.' He carries a symbolic danda (bamboo staff). His words are the signal for moving

with his group instantaneously to another place. He does not always employ this method of astral travel;

sometimes he goes on foot from peak to peak."

- Told by Swami Kebalananda to Paramhansa Yogananda in 1920, Autobiography

of a Yogi, p. 294.

It is interesting to compare stories about saintly masters who live in

mountainous regions and are

Maha-avatars or Immortals. These Superior Beings who have transcended the flesh, can

perform amazing feats

and miracles (siddhis), and possess great spiritual insight. Babaji is said to

cast no shadow, and can walk on snow or mud and not leave any footprints. Jesus Christ has some

of these amazing magical talents like disappearing in a crowd, producing food from empty

baskets, changing water into wine, walking on water, curing and consoling

the sick, and being immortal. High level wizards also have comparable

magical powers.

"According to Taoist priest Qian Xuan's research on Wudang martial

arsts, Zhang Sanfeng

over a period of time variously created Wu Ji Quan 12 postures, Tai He Quan 8

postures,

and Taijiquan 16 postures. He later fused the characteristics of all three

arts onto one, forming Taijiquan 36 postures. This boxing set was further refined over

the generations,

forming the present day 108 postures "Sanfeng Taijiquan" or

"Wudang Taijiquan." It is

recorded that and early patriarch was Zhang Songxi (Zhang Sanfeng's

disciple). Two

sentences are also recored - "Taijiquan, 13 postures" and

"Thirteen postures make

Taijiquan complete."

- Alex Yao, 2001, A New Look at T'a Chi Origins

"Zhang Sanfeng saw a burst of golden light where the clouds meet the

mist-shrouded peaks.

A thousand rays of marvelous qi spun and danced in the Great Void.

The Immortal [Zhang

Sanfeng] hurried to the spot but saw nothing. He searched where the golden

light had

touched down and found a mountain stream and cave. Approaching the mouth

of the cave,

two golden snakes with flashing eyes emerged. The Immortal swished his

duster and the

golden light came down. He gazed on it and realized that it was two long

spears about seven feet five inches. They seemed to be made of rattan, but were not

rattan; seemed

of wood, but were not of wood. Their quality was such that swords could

not harm them

and they could be soft or hard at will. A rare glow emanated from within

[the cave], and looking deeper, he found a book. Its title was Taiji Stick-Adhere Spear

and its destiny

was to be transmitted to the world. He grasped the principles of the book

and analyzed

all of its marvels. All of the words in the book were written in the form

of poems and

songs. Today we cannot understand all the principles and marvels of the

spear, but Master Zhang extracted the essence of every word and transformed them into a

series

of postures. All men can now study and learn this art."

- Quoted by Barbara Davis, The Taijiquan Classics, 2004, p. 29

Translated by Dougleas Wile, T'ai-chi Touchstones, 1993, p.

138.

"A Native of I-Chou in Liao Tung Province. An external master and court

official of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), other sources state he was born later in the Sung dynasty

(960-1279), who upon retirement retreated with disgust from the world to a Taoist monastery

on Wu Tang Mountain, where he acquired his Taoist name of San Feng. He is said to have

learned T'ai Chi Ch'uan in a dream, or after watching a bird and a snake fight. More likely,

Chang applied the Taoist health principles and knowledge of energy circulation to his vast

ability in external kung fu, thus creating something really different - a martial art that dos not

use muscle power as a primary source of movement, but Chi. Records available in the monastery on

Wu Tang Mountain do indeed mention him. Descriptions picture him as being seven feet

tall, with the bones of a crane and the posture of a pine tree (whatever that is supposed to

mean), whiskers

shaped like a spear, winter and summer wearing the same bamboo hat, carrying a

horsehair duster and being able to cover 1000 Li in a day."

- Master

Chang San Feng

"A second legend attributes the same Zhang Sanfeng to be living in the

Yuan Dynasty. In this story, while studying the mysteries of Taoism and trying to

get to grips with the secrets of immortality, he observed the posturing of

numerous animals. One day he saw a snake and crane fighting and was inspired, by the

Yin and Yang qualities of their attacks and evasions, to develop the art of

Taijiquan.

So Zhang Sanfeng is accredited with restructuring martial arts along

inspirational lines. As a Taoist monk, he connects the art with the philosophy of Yin and

Yang, the I'Ching and its Paqua diagrams. The connection between Taijiquan, Lao

Tzu, the Tao Te Ching are implicit in the legend of Zhang Sanfeng."

- Dick

Watson

"Zhang Sanfeng was a semi-mythical Chinese Taoist

priest, who is believed by some to have achieved immortality. His legend varied

from either the late Song Dynasty, Yuan Dynasty or Ming Dynasty. His name was

Zhang Junbao 張君寶, before he became a Taoist. (Zhang Sanfeng—simplified Chinese:

张三丰; ancient Chinese: 張三丰; pinyin: Zhāng Sānfēng; English spelling: Chang San-feng;

variant 張三豐. Pronunciation keeps the same.)

As a legendary cultural hero, Zhang Sanfeng is credited by

modern practicers as having originated the concepts of neijia (內家), in other

words, the soft, internal martial arts. To put it concretely, the Taichi Quan is

one of the neijia kungfu, which is the result of a Neo-Confucian syncretism of

Zen Buddhist Shaolin martial arts combined with the principles of his Taoist

neigong. In legends, he is also associated with the Taoist monasteries at Wudang

Mountains in Hubei province. Stories from the 17th century onward recorded that

he initiated the internal martial arts. In the 19th century and later, the

credit for the creation of Taichi Quan went to him.

In addition, Zhang Sanfeng is said to have been an expert in

the White Crane and Snake styles of Chinese martial arts, as well as in the use

of the Chinese straight sword. According to the documents preserved within the

Yang and Wu family's archives, the name of Zhang Sanfeng's master was Xu

Xuanping 許宣平, who was said to be a hermit poet and Taoist Tao Yin master in Tang

Dynasty.

The Taichi Quan families who ascribe the foundation of their

art to Zhang generally, and celebrate his birthday on the 9th day of the 3rd

Chinese lunar month. Owing to his legendary status, his name frequently appears

in Chinese novels and action films as a spiritual teacher and master of martial

arts."

- Wudang Kungfu

Foundation Founder Zhang Sanfeng

Return to the Main Index for this Webpage

"Mount Wudang, also known as Can Shang Mountain or Tai He Mountain, is located in the Qin Ling Mountain Range of northwestern Hubei Province. Because the scenery around Mount Wudang is so majestic and beautiful, it has been given the name 'The Famous

Mountain Under Heaven.' Wudang is a major center for the sudy of Daoism and self-cultivation.

The legendary founder of Wudang wushu was Zhang San Feng. Zhang San Feng was a Daoist who lived in these mountains to cultivate the Dao during the Ming Dynasty.

Zhang San Feng was born in 1247 A.D. in the area of what is known today as Liao Ning.

Zhang San Feng is a very famous figure in the history of Chinese wushu. His martial abilities and healing techniques were superb and he was known to have cured many people of illnesses. This brought about great admiration from the common people.

The emperor of the Ming Dynasty erected a monument on the mountain to commerate the contributions of Zhang San Feng. During Zhang's younger years he met Daoist Huo Lung (Fire Dragon) with whom he studied the Dao. After attaining the Dao, Zhang moved to Wudang Mountain and cultivated an additional nine years. Many historical documents suggest that Zhang San Feng was the person responsible for synthesizing the wushu of the common people with the internal methodology and philosphical principles of Daoism.

Wudang wushu is primarily known for its internal styles.

Zhang San Feng created Wudang wushu by researching the basic theory of Yin and Yang, the Five Elements, and the Eight Diagrams (Ba Gua). Wudang wushu has a very close relationship with the theories of Taiji, Yin and Yang, the Five Elements, the Eight Diagrams, and the Nine Palaces. Zhang San Feng was able to incorporate the Daoist practice of changing the Essence into Internal Energy , Internal Energy into Spirit,

and Spirit into Emptiness to form the theory of Wudang wushu. "

- Introduction

to Wudang Martial Arts

Return to the Main Index for this Webpage

Chang San-Feng

Patriarch of the Wu-Tang-Shan Sect of Complete Reality Taoism

"Chang the Immortal, Who Understands the Subtleties and Reveals the

Mysteries."

The

Shambhala Guide to Taoism by Eva Wong, p. 89

"When your nature is stable, energy naturally returns.

When energy returns, Elixir spontaneously crystallizes,

In the pot pairing water and fire.

Yin and yang arise, alternating over and over again,

Everywhere producing the sound of thunder.

White clouds assemble on the summit,

Sweet dew bathes the polar mountain.

Having drunk the wine of longevity,

You wander free; who can know you?

You sit and listen to the stringless tune,

You clearly understand the mechanism of creation."

- Ancestor Lu, Ancestor Lü's Hundred-Character

Tablet

Translated by Thomas Cleary, Vitality,

Energy, Spirit: A Taoist Sourcebook, 1991, p. 185.

Chang San-feng's Commentary on Ancestor Lu's

Hundred-Character Tablet, pp. 186-191.

"There are 781 male immortals and 120 female immortals recorded in Lishi

zhenxian tidao

tondjian 歷世真仙道體通鑒, or a History of True Immortals edited by Taoist

Zhao Daoyi 趙道一

in 1276. “Wudang alchemist Zhang Sanfeng” is nowhere to be found. This work is

collected

in the Taoist Canon. (Zhao Daoyi) There are 21 Wudang Mountain

Taoist Immortals

specifically recorded in Wudang fudi congzhenji 武當福地總真集, or the

Complete Biographies

of Immortals from Auspicious Wudang Mountain edited by Wudang Taoist Liu

Daoming

劉道明 in 1291. “Wudang alchemist Zhang Sanfeng” again is nowhere to be found. The

work

also is collected in the Taoist Canon. (Liu Daoming) In Yuan

yitong zhi 元一統志, or a

Cohesive History of Yuan Dynasty edited by Bei Bolan 孛勃蘭 and Yue Xuan 岳鉉,

there

are 11 prominent Buddhist and Taoist Adepts recorded, “Wudang alchemist Zhang

Sanfeng” is not to be found. The editing of this work began in 1285, and

completed in

1303. (Bei Bolan) We find no traces of “Wudang alchemist Zhang Sanfeng” in

the

following related local Gazetteers: Xiangyang junzhi 襄陽郡志, or

Xiangyang Prefecture

Annuls, (Zhang Heng) Xiangyang fuzhi 襄陽府志, or Xiangyang Prefecture

Annuls,

(Hu Jia) Huguang tujingzhi 湖廣圖經志, or the Annuls of Charts and Records

of

Huguang, (Wu Yanju) Huguang congzhi 湖廣總志, or the Cohesive Annuls

of Huguang,

(Xu Xuemo) Xiangyang fuzhi 襄陽府志, or Xiangyang Prefecture Annuls,

(Chen E) Junzhouzhi 均州志, or Junzhou Annuls (Dang Juyi), Junzhou xuzhi

均州續志, or the

Continued Junzhou Annuls, (Jia Hongzhao) Dayue taihe shanzhi 大岳太和山志,

or the Great Taihe Mountain History, (Shen Dan) Dayue taihe shanzhi

大岳太和山志,

or the Great Taihe Mountain History, (Lu Chonghua) and Dayue taihe

shanzhilue

大岳太和山志略, or the Concise Taihe Mountain Annuls. (Wang Gai)."

-

Literati

Tradition: The Origins of Taiji. By Bing YeYoung.

A person calling themselves "Sifu" wrote to me on 1/24/2006, and criticized this webpage as follows:

"Chang San-Feng was real It's very disrespectful to "portray"

Chang San-Feng as a "imagery” figure. Please don't have false information

on your Web Page... He did exist, the so called common years that he lived

(1247-1447 AD) is just a “estimated range”. Chang San-Feng (also known by

different spellings ex. Zhang Sanfeng) was the “original creator” of the 13

original movements of Tai Chi Chuan.

One just has to look, at the old book of

“The Tai Chi Classics”, to see his teachings.

It not only, insults the

original master, of all forms Tai Chi Chuan, but it also shows lack of

knowledge, history, and understanding of the art. I hope you remove all false

references about him, from your website. I am from direct Yang family lineage. Thank You for reading the above. Sifu"

[I did write back to "Sifu," however the email [not@happy.com]

bounced. I do believe

that my webpage does try to give a fair and reasonable accounting of the

stories

and legends about Master Zang San Feng. A number of experts and scholars argue

that Zhang San Feng is not the inventor of Tai Chi Chuan internal

martial arts, and place its origins in the Chen style of Tai Chi Chuan. ]

"It was said that Zhang-Sanfeng,

originally named Zhang-Quanyi, nicknamed Sanfeng, was born in Yizhou City,

Liaoning Province and was tall and strong, with tortoise shape and swan bone,

big ears and round eyes, hard beards and moustaches. He always wore a coir

raincoat and a pair of straw scandals. No matter in summer or winter, he lived

in the lonely and deep mountains or traveled in the crowded cities. He could

remember what he had read just by one look and talked nothing but moral,

kindness, faith and filial piety. He could talk with the gods and understand

Taoism, so he could forecast the future and solve all the difficulties in the

world. He could live without a meal for five days, even for two or three months;

He could penetrate the mountain and drive the stones when he was happy; he lived

in the snow when he was tired; He traveled here and there without any trace, so

all the people at that time were amazed at him and thought him one of gods.

Wudang Taoist medical cultivation has a long history,

especially the inner medicine, which is to cultivate the breath into medicine so

as to make one strong and healthy, and prolong the lifespan by way of breathing.

Zhang-Sanfeng had a profound cultivation in inner medicine. He said in On

Taoism"To cultivate the mood before cultivating the medicine; to cultivate the

character before cultivating the good medicine; when the mind is steady, the

medicine will come naturally by itself; when the mood and character have

cultivated, the good medicine will be in reach", which figuratively explained

the progress of medicine cultivation. He had written many books on medicine such

as The Gist of Gold Medicine, The Secrecy of Gold Medicine, A Song of Inner

Medicine, Twenty-four Principles of Rootless Trees, Taoist Song of Earth Element

and Real Immortal, which had been published in the Ming Dynasty. Later, the

people had compiled them into The Full Collection of Zhang-Sanfeng's Works, with

eight volumes.

Zhang-Sanfeng was not only profound in medicine cultivation

but also in martial art, especially good at boxing and swordplay. He, on the

base of Taoist theories, such as the naturalness of Taoist theories, keeping in

a humble position and so on, had combined Taoist internal exercises, guarding

skills of regimen, boxing acts of martial art, military sciences of militarists

into one, and then created Wudang Boxing, which takes the internal exercises as

the body, attacking as the purpose, regimen as the first important thing,

self-protection as the main principle, and to defeat the tough with a tender

act, charge the active by the still movement and attack the opponent with his

own force, strike only after the opponent has struck. From the Ming Dynasty,

martial art world have respected Zhang-Sanfeng as the founder of Wudang Inner

Boxing and Taiji Boxing. Wudang martial art, through many generations'

succession and development, has become one important school among China martial

art and spread in the folk with a long and profound influence."

- The

Founder of Wudang Tai Chi Zhuan - Zhang San-Feng

"Chan San-Feng has become a mythical figure, but so has Jesus, and look

what is said about everything he did! I think that Chan San-Feng did exist, as

Taijiquan was passed from Master to Student heart to heart, so it must have started in a

human heart. It is just that the early forms of religion were magical and mythical in

nature; in the verbal story telling tradition. I am sure they were both real

characters. I have

also studied the San-Feng Taijiquan from the Wudang tradition with Máster Tian

Liyang from Wudang since 2000. So I have a bit of direct background knowledge,

most of it is in German. If you want to know more about the subject I can

recommend "Wudang – Mountain of the Immortals" from Abbot Wang Guangde, which

also has an English version."

- Philip Stanley, Qigong,

email 1/30/06 to Mike Garofalo

"While kungfu was developed as an external,

combative form of physical discipline, Zhang San-feng (living sometime

in the period 960-1279 AD) was creating a technique that would make him a

legendary patriarch of latter-day Tai Chi Chuan. He is often attributed to the

time of Song Dynasty, though the most reliable and accepted evidence indicates

that Zhang San-feng was the former magistrate and scholar of Confucianism for

Chung Shan County, and was a native from Yi Zhou in today's east Liaoning

Province. According to this evidence, he was born on the ninth day of the fourth

moon of 1247 AD, in the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368AD).

His fame became established after he had completed a ten-year devotion

at the Shaolin Monastery where, besides studying the Chinese Buddhist doctrines,

he learned the " exoteric martial arts," wai kung . Zhang San-feng went

on to study Taoism at the K'o Hung Mountain Monastery, which led him to wander

as a hermit until he reached the Taoist enclave at Wudang Shan, sometimes

referred to found in Hubei Province. Here he founded the first major esoteric of

internal school, nei kung , of martial arts. This was the birthplace of

modern Tai Chi Chuan.

A Chinese Merlin, Zhang San-feng laid out the initial moves of the Tai

chi form, based on inspirational and dreams he had experienced. Composed much

later, the Tai Chi classics state that one night he dreamed of a Taoist Immortal

advising him to reform his strenuous training methods, to relax the rigors he

had developed as part of his earlier Shaolin training. The message of the dream

troubled him for a long time, until one day he spotted a snake and a crane in

deadly combat.

The snake and the crane also have a magical significance in

the West. Having deciphered obscure Western alchemical texts, Jung found that the

snake symbolized the "chthonic," with earth energy represented as a dragon or

physics, which makes up the element equivalent to yin in Chinese philosophy.

Distinct from this creeping reptile, the crane stands for the aerial, the

spiritual, psychic energy that is the yang principle. Therefore, the snake and

the crane present two principle opposites of Nature in both Chinese and European

alchemy. In Tai Chi Chuan, the Snake Creeps down has a martial application, but

it also signifies the descent into Underworld. "Redemption" takes places in the

next move, when the " Golden Bird (crane) stands on One leg," portraying the

ascent of the spirit. These movements, then, comprise paradise lost and found"

- Zhang San Feng,

Wudang Taoist Culture Center.

"After verification according to different historical materials, Zhan

Sa-Feng, with the original name Zhan Jun-Bao and the Taoist name Yu-Xu Zi, is now known to be of

the

Song Dynasty. He was indifferent to fame and wealth and had no interest in

the official career given by the authorities. After declining an official

position and dispatching

his property to his clan, he traveled around the country.

He stayed at Hua Mountain in northwestern China for several years to deepen his

own self-training. Afterwards, he left Hua Mountain and lived on Wu-Dan Mountain

in Central

China, leading a hermit's life.

Zhan Sa-Feng was versed in Shao-Lin Gong-Fu from a young age. After

contacting the internal Gong-Fu transmitted from the line of Li Dong-Feng and Jia De-Shen, he

changed

his ways and turned to internal cultivation. He concluded four principles

about his own

system: First, control motion with repose. Second, conquer hardness

with softness. Third, surmount swiftness with uniformity. Fourth, overcome the many with

the few.

Thus Zhan Sa-Feng composed a complete internal Gong-Fu system. Because

this internal

Gong-Fu was explained with ancient Tai-Ji principles, it is called Tai-Ji

Gong-Fu by the people."

- Albert Liu, Nei Jia Quan: Internal Martial Arts, 2004, p.

318

"Taoism has a complicated system of

immortals and deities. They fall roughly into three categories: natural gods,

such as those of the sun, moon, wind, rain, and earth; deified mortals of great

merit, such as role models for fidelity, filial piety, benevolence and justice;

and daily functional gods, such as the door, kitchen and fire gods. Each has its

own characteristics, but all represent justice and benevolence and have the

common purpose of helping the needy and punishing evildoers.

Unique among the large body of immortals believed to live on

Wudang Mountain was the martial Taoist monk, Zhang Sanfeng. He could walk 500

kilometers daily, fast for months at a time and vanish and reappear in an

instant, according to The History of the Ming Dynasty. The founding emperor of

the Ming Dynasty Zhu Yuanzhang had tried unsuccessfully to employ Zhang Sanfeng

in his service, but the monk was notoriously difficult to pin down. Emperor Zhu

Di wrote an extraordinarily modest and respectful letter to Zhang Sanfeng,

requesting a meeting, but Zhang declined. No mortal that valued his life would

have dared to behave in such an offhand manner towards the emperor, but as Zhu

Di regarded Zhang Sanfeng as a deity he was not affronted. On the contrary, to

express his sincerity, the emperor ordered construction of the Yuzhengong

(Meeting the True Man Palace) on Wudang Mountain and the enshrinement of a

statue of Zhang Sanfeng in its main hall. This unheard of imperial honor caused

a storm of speculation as to the emperor’s motivation for such an act of

obeisance. Some thought it was because Zhang Sanfeng was actually a living deity

versed in the arts of necromancy and distillation of life-prolonging elixirs.

Others surmised that Zhang knew the whereabouts of the missing emperor Jianwen,

whose reappearance was the emperor’s greatest dread. Since the Zhu Di epoch,

however, Zhang Sanfeng has been regarded as a great martial artist and founder

of Wudang kungfu, rather than immortal.

Wudang kungfu is equal in reputation to Shaolin kungfu, the

former being generally accepted as the southern, defensive and the latter as the

northern, offensive school of martial arts. One of Zhang Sanfeng’s most esteemed

contributions to Chinese martial arts was his unequivocal statement that the

ultimate purpose of practicing kungfu was to maintain physical health. Taoists

were popularly associated with elixirs and alchemy, but Zhang Sanfeng was one

outstanding exception. In a letter to Emperor Zhu Di he wrote, “It is better not

to believe in alchemy and alchemists….. The amplitude of Dao and abundance of

virtue are the best remedies, and a serene mind and absence of desires bring

longevity.” Zhang created and practiced an “inner elixir kungfu,” known today as

qigong, or respiratory kungfu -- a breathing technique that aligns the body and

the spirit."

-

Mount

Wudang Abode of the Immortals and a Martial Monk

"In the Chinese history there existed two men called Zhang San Feng. One

was born in the Sung dynasty (960-1279), who upon retirement retreated with disgust from the

world to a Taoist monastery on Wudang Mountain, where he acquired his Taoist name of

San Feng.

He is said to have learned T'ai Chi Ch'uan in a dream, or after watching a bird

and a snake fight. More likely, Zhang applied the Taoist health principles and knowledge of

energy circulation to his vast ability in external kung fu, thus creating something

really different - a martial art that dos not use muscle power as a primary source of movement,

but Chi.

Later he became an accomplished Inner KungFu master after long term practice

with several teachers. Therefore, he was regarded as the common founder of all

Taichi boxing schools.

Another Zhang San Feng was a native of I-Chou in LiaoTung Province. His scholar

name was Chuan Yee and Chun Shee. He lived in Yuan dynasty (1279-1368).

The Chinese old book Ming History bearing records available in the

monastery on Wudang Mountain does indeed mention him. Descriptions picture him as being seven feet

tall, with the bones of a crane and the posture of a pine tree, whiskers shaped like a

spear, winter and summer wearing the same bamboo hat, carrying a horsehair duster

and being able to cover 1000 Li in a day, sometimes eating 50 Kg food in one

meal, sometimes keeping fasting as long as several months, possessing amazing memory as to recite a scripture fluently after reading it just one time."

- Mount Wudang

and Wudang Kung Fu

"Chang San-feng was born sometime

between 600 and 1600 AD, perhaps sometime during the Sung Dynasty, or maybe the

Yuan Dynasty, but exactly at midnight on the fourth of April, 1247, and he lived

precisely between the years 960 and 1126. His family came from I-Chou in the

Liao-tung Peninsula. He spent many years at the Temple of the Jade Void,

becoming expert in Shaolin kung fu. Early on, it was discovered that he could

recite Taoist classics after only a single reading. As he traveled, he became

wise in the meditative and martial arts. At the age of sixty-seven, he

retired to the Wu Tang Mountains, where he built himself a cottage. At rest, he

meditated, returning to the Original Source; when active, he roamed the Three

Mountains and the Five Peaks, gleaning the finest elements and subtle chi of

Heaven and Earth and circulating them with breathing exercises. During this

time, his reputation spread far and wide. The first Ming emperor sent a

messenger to find him and bring him to court, but the errand was unsuccessful.

Throughout his life, Chang took pains to conceal his

achievements. He did not want to appear at court and so worked hard to seem mad.

Everyone agrees that he did not keep himself neat and clean; Chang Lar-tar

(Sloppy Chang) or La T’a (Dirty Fellow) often acted as if no one was around,

spitting, farting, and scratching. He liked to tease people. He was very

virtuous and often displayed such great mirth that is was impossible to remain

melancholy in his presence. Winter and summer, he wore the same rude bamboo hat,

the same old, ragged priest’s robe. Instead of a staff, he carried a horsehair

broom. Sometimes he would eat a bushel of food at a time, then again, he

wouldn’t eat for weeks. He never ate grains or cereals at all.

His picture can be seen at the White Cloud Temple in Beijing.

He was seven feet tall, had bones like a crane; his posture was like a pine

tree, his face round like an ancient moon, with kind brows and generous eyes and

whiskers shaped like a spear; he was a big man, shaped like a turtle (a symbol

of longevity), with a crane’s back, large ears, round eyes, and beard like the

tassel on a spear. He was very tall, his beard reached his navel, his hair

touched the ground.

He had six hobbies: sword playing in moonlight, playing tai

chi in the dark, mountain climbing on windy nights, reading the classics on

rainy nights, meditating at midnight in the full moon, and playing the lute.

One day, the Immortal suddenly saw a burst of golden light

where the mists shrouded the peaks. A thousand rays of chi spun and dance in the

Great Void. He searched where the golden light touched down and found a mountain

stream issuing from a cave. Approaching the cave, he saw two golden snakes with

flashing eyes. He swished his horsehair duster and realized that they were

really two spears of such quality that swords could not harm them. Master Chang

also discovered in the cave a glowing book of songs and poems from which he

extracted the essence, transforming them into the postures of the art of tai chi

spear.

Chang used the movement “diagonal flying” to break firewood

in the forest, and he had a large pet ape who collected his firewood for him. In

fact, the ape so often had an opportunity to watch the Master practice that, in

faithful imitation, he developed a simian version of tai chi. Upon being

attacked by a python, Chang grasped the serpent at either end, and using the

technique of “parting the wild horse’s mane,” he tore it into pieces. Once,

encountering a tiger in the mountains, he applied the skill of “bend the bow to

shoot the tiger”—first he turned to avoid the tiger’s rush, then grasping the

two hind legs as the beast passed, he tore it in half."

-

Chang San-Feng: His

Life and Deeds. By Jack McGann and Christopher Dow. An

apocryphal biography of the legendary founder of Tai Chi Chuan. An

interesting short biography with some new stories about Master Zhang.

Wudang Mountain Temple

"The Wudang Mountains (Simplified Chinese: 武当山; Traditional Chinese:

武當山; Hanyu Pinyin: Wudāng Shān), also known as Wu Tang Shan or simply Wudang, are a small mountain range in the Hubei province of China, just to the south of the manufacturing city of Shiyan.

In years past, the mountains of Wudang were known for the many Taoist monasteries to be found there, monasteries which became known as an academic centre for the research, teaching and practise of meditation, Chinese martial arts, traditional Chinese medicine, Taoist agriculture practises and related arts. The monasteries were emptied, damaged and then neglected during and after the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, but the Wudang Mountains have lately become increasingly popular with tourists from elsewhere in China and abroad due to their scenic location and historical interest. The monasteries and buildings were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. The palaces and temples in Wudang, which was built as an organized complex during the Ming dynasty (14th–17th centuries), contains Taoist buildings from as early as the 7th century. It represents the highest standards of Chinese art and architecture over a period of nearly 1,000 years."

- Wudang Mountains - Wikipedia

"Twentieth-century martial arts historians Tang Hao and Xu Zhen in

independent efforts

disputed the role of Zhang Sanfeng as founder of taijiquan, as have others

since. We can

see that not only does the internal evidence of the Taijiquan Classics

contradict Zhang's

role, but Chen family material, ostensibly earlier and closer to the source, has

no record

of Zhang, regardless of the assertion that the founder of Chen style is said to

have incorporated "Daoist ideas" into his proto-taijiquan style.

Moreover, if Zhang had invented taijiquan, we would expect to find trace of Zhang in Chen Family

Village, or

to find traces of taijiquan in other locales in which Zhang and his followers

may have

been. Additionally, neither Zhang's official biographies nor his

attributed writings on

Daoist topics mention boxing. Portraits of Zhang, no matter how far

removed in time from when he lived, or how generic the style of painting, always depict Zhang in

a

contemplative stance, with no hint of boxing in the picture."

- Barbara Davis, The Taijiquan Classics, 2004, p.

18.

"The origins of Tai Chi Chuan go back to around the Sung Dynasty (960-1279) in China. As the story goes, Chang San-feng, a Taoist priest, was meditating on Wu-Tang Mountain, in Hupei province. One day he heard a noise outside and found that a bird was attacking a snake. Chang watched as the bird attacked the snake's head and the snake yielded at his head and struck with his tail. Then the bird attacked the snake's tail and the snake yielded at his tail and attacked with his head. When the bird attacked the snake's belly the snake yielded at the belly and attacked with both his head and his tail. In the end the bird gave up and flew away. Chang was so impressed with the beauty and efficiency of the snake's defense that he decided to create a martial art using the yielding (yin) and attacking (yang) method of the snake. He combined the thirteen postures with Taoist philosophy and exercises to create Tai Chi Chuan. Chang then wrote what is known as the Tai Chi Chuan

Classic, a very important read for those studying Tai Chi Chuan."

- Kent's Tai Chi Center, The

Thirteen Postures

"The evidence for the existence of Zhang San Feng is impressive,

although some scholars say

that he was a myth. Erected on Wudang Mountain are two huge stone tablets

honoring him as a Taoist saint, one decreed by the Ming Emperor Seng Zu, and the other by the

Ming Emperor Ying Zong. The Imperial History of the Ming Dynasty records

that Zhang San Feng

was born in 1247, learned Taoism from a Taoist master called Fire Dragon at

Nanshan Mountain

in Shenxi, cultivated his spiritual development for nine years at Wudang

Mountain, was known

by the honorific title of "the Saint of Infinite Spiritual Attainment', and

was the first patriarch

of internal martial arts. The Records of the Great Summit of Eternal

Peace Mountain mentions

that he studied the yin-yang of the cosmos, observed the source of the longevity

of tortoises

and cranes, and attained remarkable results. Collections of Clouds and

Water describes him as

carrying his lute and sword on this back, singing Taoist songs, work in the